Joel Polack: 7, Back to New Zealand

Joel Polack’s father, Solomon Joel Abraham Polack, a noted artist, miniaturist and engraver. died on August 30, 1839 in London. Born The Hague in 1757, he was buried in the Brompton Jewish Cemetery. With Joel’s father dead, his book completed, there was nothing to keep him in England. A brother and a sisters of his were in Australia. He still had property and business interests in New Zealand that his associate, Thomas Spicer looked after, so he sailed back and arrived in the Bay of Islands on the Brig Caroline from Sydney. On 31 August 1841. Before leaving London he would have packed up his father’s collection of art works, which would have included a portfolio of drawings, etchings, and engravings by his father and grandfather, as well as works by some seventeenth and eighteenth century artists. Over the years he had accumulated a substantial collection of travel writing, both published and in manuscript. He had everything for a comfortable establishment at the Bay of Islands. However, during the four years between leaving New Zealand in 1837 and returning in 1841, New Zealand experienced great changes. Immigrants were flooding in. When he left New Zealand in 1837 there were fewer than 2000 Europeans living there. After 1840, the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the start of the campaign of the New Zealand Company to promote settlement, Europeans arrived in very large numbers, so that a mere ten years later there were some 26,000 Europeans living in the land. The centre of population and the capital moved from the Bay of Islands to Auckland. Kororareka, a name which meant in Maori “how sweet is the penguin” 1 was renamed Russell, after Lord John Russell, Secretary of State for the Colonies. The hub of business and enterprise moved to the new capital and the Bay of Islands languished. In 1842 Auckland was designated as the first capital of New Zealand and immigrant ships began to arrive. By 1842, within two years of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and British colonization, the population of Auckland reached almost 3000. The principal native tribe, Ngāti Whātua of the Auckland region, encouraged European settlement, hoping that this would afford them protection from the threat of the more powerful Northern tribe of Ngapuhi, and also saw of the commercial advantages of more Europeans settling in the region. While Auckland thrived, the Bay of Islands stagnated. Whaling, which in 1838 brought 54 American ships along with 14 British, 18 French and 10 from Sydney, with their crew and demands for refitting, virtually ceased after 1842. Auckland was becoming the centre of commerce. Polack looked for new business opportunities. But first he had to attend to the recognition of his land purchases by the new colonial government.

The Land Claims Ordinance 1841 established the Native Protectorate Department to prevent settlers fraudulently taking land from Māori. Polack had to establish his rights to properties he had purchased over the years. Some of them didn’t amount much, some were considerably larger, but none were large enough to suggest that he engaged in land speculation on any scale, nor did he plan to settle or cultivate any of them. He was not really a settler. He couldn’t stay still in any place. He bought 100 acres in the Bay of Islands, purchased in 1833, and also that year nine and a half acres on Kororareka beach where he built his home and warehouse, some land in Waitangi, bought in 1835, and more on the Waitangi River bought a year later, and another portion of land situated on the northern extreme of Kororareka Beach. In each case the names of the sellers, in most cases a number of natives with an interest in the land, were named and the amount Polack paid for it.

While his main preoccupation on his return to New Zealand was establehisng his claims to lands he purchased, he also engaged in his trading activities, though probably on a much smaller scale than he did before her left New Zealand. The Auckland Chronicle noted on 29 November 1843 that while settlers in Nelson hoped that there would be some flour on board of the ship that had arrived from London, there were only ten barrelles for Mr. J Polack.

However after the capital of New Zealand was moved from Kororareka in the Bay of Islands to Auckland, Ngapuhi and other Maori tribes in Northland were in turmoil. The number of ships coming to the Bay of Islands declined, the dues the Maori tribes collected from these were reduced, profitable trade with the whaling ships was lost, and the new government imposed duties on spirits, tobacco tea, sugar, flour, and firearms, goods that the natives purchased. There was a vague but widely diffused belief that the Treaty of Waitangi was merely a ruse of the pakeha, and that it was the secret intention of the whites, so soon as they became strong enough, to seize upon the lands of the Maori1.

Hone Heke, a Ngapuhi Chief, was a reluctant signatory of the Treaty of Waitangi. He remembered the dying words of his uncle, Hongi Ika, the great warrior chief 2

“Children and friends, pay attention to my last words. After I am gone be kind to the missionaries, be kind also to the other Europeans; welcome them to the shore, trade with them, protect them, and live with them as one people; but if ever there should land on this shore a people who wear red garments, who do no work, who neither buy or sell, and who always have arms in their hands, then be aware that these are a people called soldiers, a dangerous people, whose only occupation is war. When you see them, make war against them. Then, O my children, be brave then, O friends, be strong! Be brave that you may not be enslaved, and that your country may not become the possession of strangers. “3

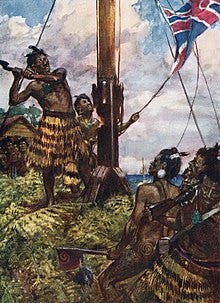

Hone Heke saw the flagstaff erected on the hilltop overlooking Kororareka as the manifestation of the threats that Hongi Ika warned him about. He cut down the flagstaff, the symbol of British occupation. After the British replaced it, he cut it down again and cut it down yet again a third time. The British tried to assert their authority. Confrontation ensued. Shortly before dawn on 11 March 1845, Heke and about 450 warriors moved on Kororareka. One group, led by Te Ruki Kawiti, 4 the notable Nga Puhi chief, warrior and a skilled military tactician. created a diversion, enabling Heke to seize the blockhouse that defended the flagstaff. The offending pole was cut down for the fourth and final time.5

Some weeks before the conflict, the Chief Police Magistrate of Kororareka, Thomas Beckham, asked Joel Polack, to allow his premises to be used for the protection of the inhabitants of the town, (by then renamed Russell) in case the town was attacked. These premises, located on the foreshore, comprised a large house with 2 upper rooms and 12 lower rooms, a cottage with 2 upper rooms and 4 lower rooms, which housed a ship chandlery, a brewery, and a cellar. This, apart from Government House in Auckland, was the largest building complex in the colony. It had been the headquarters of the Kororareka Association in 1838, the first organization to attempt to enforce law and order in the lawless settlement. In the 1840s, at the time of Hone Heke’s and Te Ruki Kawiti’s attack, it housed the Supreme County Court, with a Grand Jury room, a Petty Jury room, and rooms for the magistrate. In its way, it embodied Joel Polack’s vision of an orderly civil society governed by the rule of law in that beautiful remote corner of the world.

It was ironic that it was Hone Heke who launched the attack on Kororareka that ultimately led to the destruction of Polack’s property. Polack’s association with Heke went back many years. He bought the land, a 9-acre strip on the beach he called Parramatta, on which his premises were located, from Heke and others on 30 August 1833, and Heke’s signatures appeared on most of Polack’s land purchases. Heke and Polack did a lot of business with each other, and it is likely that when Heke wanted to purchase some significant items from Polack he offered to sell land to him, land that he had acquired through conquest, in exchange for goods.6 Polack paid Heke and the others who had claim to the strip of land on the Kororareka foreshore, four muskets, two 25 lb. casks of gunpowder, eight blankets, four cartouche boxes and belts, six clasp knives, two pairs of scissors, two head combs, two tack combs, two large iron pots, and thirty large sheets of paper.

Polack was a prominent advocate of colonization. He believed that a well functioning, law-abiding society could evolve only through British rule. He argued this in the two books he published while in England from 1837 to 18427, and in his submission to the Select Committee of the British House of Lords on the expediency of regulating the settlement of British subject in New Zealand8. The Bay of Islands that in the early 1830s was regarded as the hellhole of the Pacific, a dangerous place where Europeans lived with the threat of unpredictable attacks by savage cannibals was home for only a few Europeans, mainly of the lowest sort, escaped convicts, unruly seamen, apart from the missionaries. The place changed significantly after the skirmishes remembered as the ‘Girls War‘ of 1830. This was the last notable tribal conflict in the Bay of Islands. With the arrival of resident traders, Polack among them, a middle class began to develop, for whom law and order was essential if their newly acquired estates were to be protected and allowed to prosper9.

In this evolving small community, Polack endeavored to be a model citizen. He donated land for the erection of a church to serve the settlers10. When the settlement was threatened he considered it appropriate to put his premises at the disposal of the Government without stipulating (sic) for any remuneration for their use, [his] sole desire being to render what [he] possessed serviceable to the Government and the inhabitants of Russell11.

During the confrontation with Hone Heke’s fighters, there were a hundred armed civilians in Polack’s stockade, as well as women and children12. Polack himself had probably spent much of his time in Auckland, pursuing his business interests there, but at that time in 1845, he was in Russell, the former Kororareka. In the early afternoon of the day of Hone Heke’s attack, the powder magazine that was stored at Polack’s Stockade exploded, possibly because one of the armed volunteers lit his pipe. Surrounding buildings caught fire.13 Two people were killed; Polack himself was injured in the explosion and all his possessions were lost.

The estimated value of his losses was £2600.14 It was possible to put a value on the cost of the buildings, the furniture and other chattels, the £600 in cash and scrip, which had to be stored on the premises as there was no bank in Russell, but no value could be put on his manuscripts, his own writing, and his works of art, including his own sketches.

He had two polished cedar bookcases each 8 feet by 4 feet on which he had numerous literary works. These included in manuscript a History of Mauritius and Madagascar collected from his personal travels, 700 papers, drawings from his own sketches in two volumes, accounts of his journeys in New Zealand, United States and various parts of the world, including some 30 voyages with nearly 1000 drawings in 3 thickly bound volumes, the manuscript of his work on the Australasian Islands published for him by chapters in the Colonial Magazines of 1839, 40, and 41 15. The books that were lost reflected his wide reading: Shakespeare, Byron, Pope, Guizot, Voltaire, Feilding, Smollett and Marriot, a Hebrew library of 12 volumes, books in Latin and French, several dictionaries, not to mention the Builder’s Almanac.16

He also lost his collection of art works and artist’s material, which included a small portfolio of drawings and etchings in copper, several miniatures, including one by Samuel Oliver (1648), who was renowned for his portrait of Oliver Cromwell, and miniatures and by Polack’s father, also a successful painter of miniature portraits, and by his grandfather, several sketchbooks and tracings, a portfolio of engravings by the eighteenth century artist, William Wollett, and more recent artists, L’Estrange, Henry Bryan Hall, James Heath, Charlton Nesbit and others, numerous charts and maps and engravings within Lizar’s Edinburgh Geographical General Atlas, and architectural drawings. Polack was the son and grandson of artists. He was also a discerning collector. As an artist himself, he would have greatly regretted the loss of his artist’s material, Bookmans pencils — oil and watercolour brushes, drawing instruments, drawing papers and quills17. Such essential material for an artist would have been hard replace.

Polack was 38 years old. His lifetime’s work had gone up in flames. He saw himself as a writer, traveller, artist, scholar, and incidentally, a successful businessman. Others might have thought of him as a land speculator, a grog seller, a Jew and a person who was not to be trusted. He was an oddity in the rough colonial frontier society, but he was almost certainly the most widely read, educated person in the land, with his own clear view of the future of the settlement. With the destruction of his writings, his works of art, the accumulated records of his many years of travel and adventure, his losses were devastating.

Polack applied for compensation and pursued his claim for years. His claim was not even acknowledged until he sent several insistent reminders some time later. The Governor, Sir George Grey, and Beckham, the Police Magistrate, who had first had knowledge of the incident, agreed that Polack had a sound case for compensation, but the matter was referred to the newly formed Legislative Council where the question of whether the loss was due to the actions of the British armed forces or a drunk local armed volunteer was debated. Twenty years later, in 1865, the issue still remained unresolved. Polack was greatly aggrieved.

It was not surprising that he considered that he had deserved better, that his losses, which were incurred because of his willingness to help the settlers of Russell, warranted not only compensation, but also perhaps recognition of his civic mindedness. He was a substantial property owner and the biggest taxpayer in his time, but twenty years on, Kororareka was seen as a distant backwater by the legislators in Auckland, the first skirmishes of the Maori Wars in the Bay of Islands paled into insignificance compared with other the battles of the time, and the Jewish trader, writer, artist and his eccentric personality faded from memory.

1Korareka — meaning Google https://www.google.com/search?q=kororareka+meaning&rlz=1C1CHBF_enNZ988NZ988&oq=Kororareka+&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUqCQgAECMYJxiKBTIJCAAQIxgnGIoFMgYIARBFGDkyBwgCEAAYgAQyBwgDEAAYgAQyBwgEEAAYgAQyBggFEEUYPDIGCAYQRRg8MgYIBxBFGD3SAQozNDkxMTdqMGo3qAIAsAIA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8